A Giant of Journalism Gets Half its Budget From the U.S. Government

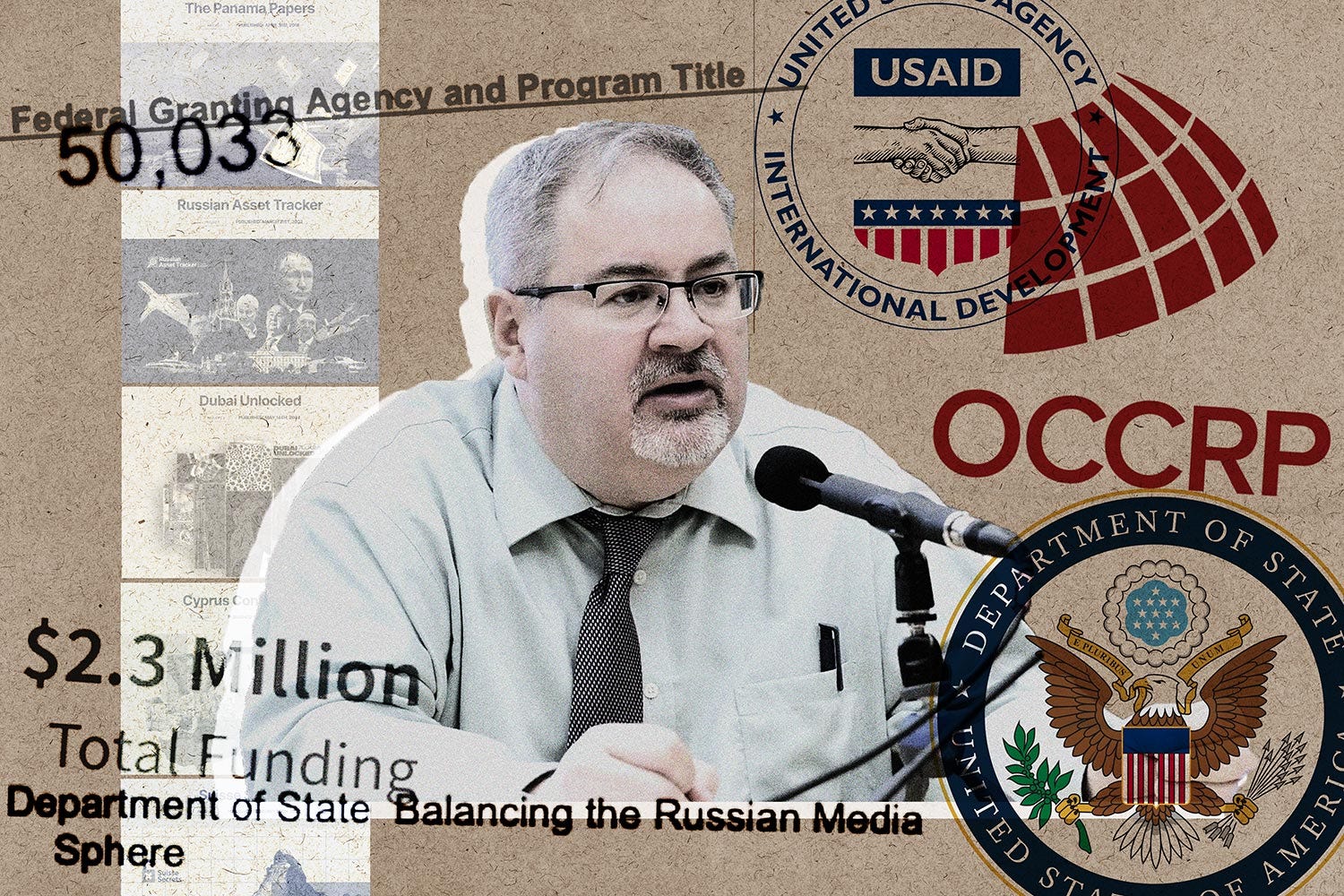

Drew Sullivan is unknown to the broad public, but the head of the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project is one of the most influential journalists in the world.

The story we’re publishing today is the product of a months-long investigation by a consortium of independent news organizations in Europe who partnered with Drop Site News here in the United States. It’s a look at the largest and most powerful news organization you’ve probably never heard of, called OCCRP—the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project. OCCRP works with dozens of major newspapers to collaboratively publish the kinds of scoops you’re well aware of, such as the Panama Papers or the Pandora Papers. What we can reveal today is that the single largest funder of OCCRP is the U.S. State Department. That and much more is in our story below.

The story is a combined project of the independent French powerhouse investigative outlet Mediapart, the storied Italian outlet Il Fatto Quotidiano, Drop Site, and Reporters United in Greece. It was launched by the German public broadcaster NDR, which has collaborated with OCCRP in the past and, under pressure from the organization, has not published its own version of the investigation.

The news outlets involved in this project, including Drop Site, have been on the unpleasant end of increasingly aggressive legal threats from Drew Sullivan, co-founder and head of OCCRP. We suspect that after he reads the story itself, he’ll conclude that it is fair, accurate, and judicious, and that there is no merit in such a lawsuit. If he decides otherwise, we will keep you apprised (and plead for money to fund the legal defense, of course). While we strived to be as fair as possible, and have posted most of Sullivan’s responses, what we’re not going to do, of course, is back down to threats, even ones backed with the resources of the federal government.

It’s the strength and commitment of our audience that gives us the confidence to publish in the face of these threats. If you haven’t yet become a paid subscriber, please consider doing that today.

And as you think of your end-of-year charitable giving, don’t forget that contributions to Drop Site are tax deductible—though with the incoming administration, who knows how long that’ll be the case.

We’re no strangers to legal threats—much of what we do angers powerful people with tools at their disposal to hit back—but these threats have been among the most dumbfounding. As you’ll see in the article, it is based on publicly available documents and on-the-record interviews, including with Sullivan himself, who confirmed the thrust of our findings.

Perhaps ironically, OCCRP helps fund Reporters Shield, a State Department-backed program aimed at defending investigative journalists against lawsuits meant to silence reporting. “Reporters Shield is an innovative solution to the increasing burden of bogus lawsuits against investigative journalism,” the program boasts. (Drop Site considered joining Reporters Shield, which seeks to address a genuinely threatening phenomenon, before learning of its government connections.)

Some of the quotes in this article are from transcriptions of on-camera interviews and conversations made between June and September 2023 by NDR journalists John Goetz and Armin Ghassim, and replies to questions sent to NDR by the OCCRP’s board of directors in September 2024. Ghassim later joined us as a fellow at Drop Site News.

USAID and Transparency International sent written replies to our questions. The US Department of State, the Open Society Foundation and Camille Eiss did not respond to questions sent to them.

Before the publication of our articles, Sullivan accused us of using methods he described as “malicious and unprofessional.”

He also attempted to denigrate two journalists who took part in this investigation. He firstly targeted NDR reporter John Goetz, describing him as a possible “Russian asset.” He then launched serious accusations against Romanian freelance journalist Stefan Candea, a co-writer of this investigation, notably because he works part-time as a coordinator for the media network European Investigative Collaborations (EIC), which may be considered to be a rival of the OCCRP.

The EIC did not take part in this investigation. Mediapart and Reporters United are members of the EIC, and the other co-writer of this report, Yann Philippin, sits on the EIC board. Yet those connections with the EIC do not represent a conflict of interest given that most media report on other media, and therefore their competitors.

Sullivan also accuses Stefan Candea of leading a personal vendetta against the OCCRP. “Stefan Candea, who appears to have played a critical role in the development of your article, has had personal conflicts with OCCRP and business relationships with one of the OCCRP founders. The journalists among us would have precluded the participation of someone with such obvious conflict,” said the OCCRP board of directors in a written statement to us.

We firmly reject these allegations which constitute an attempt to divert attention from the facts by trying to discredit some of the journalists who discovered them.

Drama aside, the story stands by itself.

—Ryan Grim

A Giant of Journalism Gets Half its Budget From the U.S. Government

By Ryan Grim, Stefan Candea, and Nikolas Leontopoulos

One of the world’s most influential global investigative news organizations, whose work has regularly produced political shockwaves, has been primarily funded since its launch by the United States government, according to a review of budget documents, audit reports, and interviews with its founder and government funders.

In the world of investigative journalism, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) is a known quantity: a nonprofit news outlet backed by civic-minded philanthropists—a ProPublica, but for global corruption. “Investigative reporting has to be a global phenomenon. It takes a network to fight a network of corruption. And OCCRP is that network,” said Drew Sullivan, co-founder and head of OCCRP. "It's the most important investigative reporting organization you've never heard of.”

What has thus far been obscured from the public is the magnitude of its government funding and the strings attached to it. OCCRP’s founding and most generous donor, the one responsible for a majority of the organization’s budget, is the government of the United States and within the government, the largest donor is USAID—the U.S. Agency for International Development.

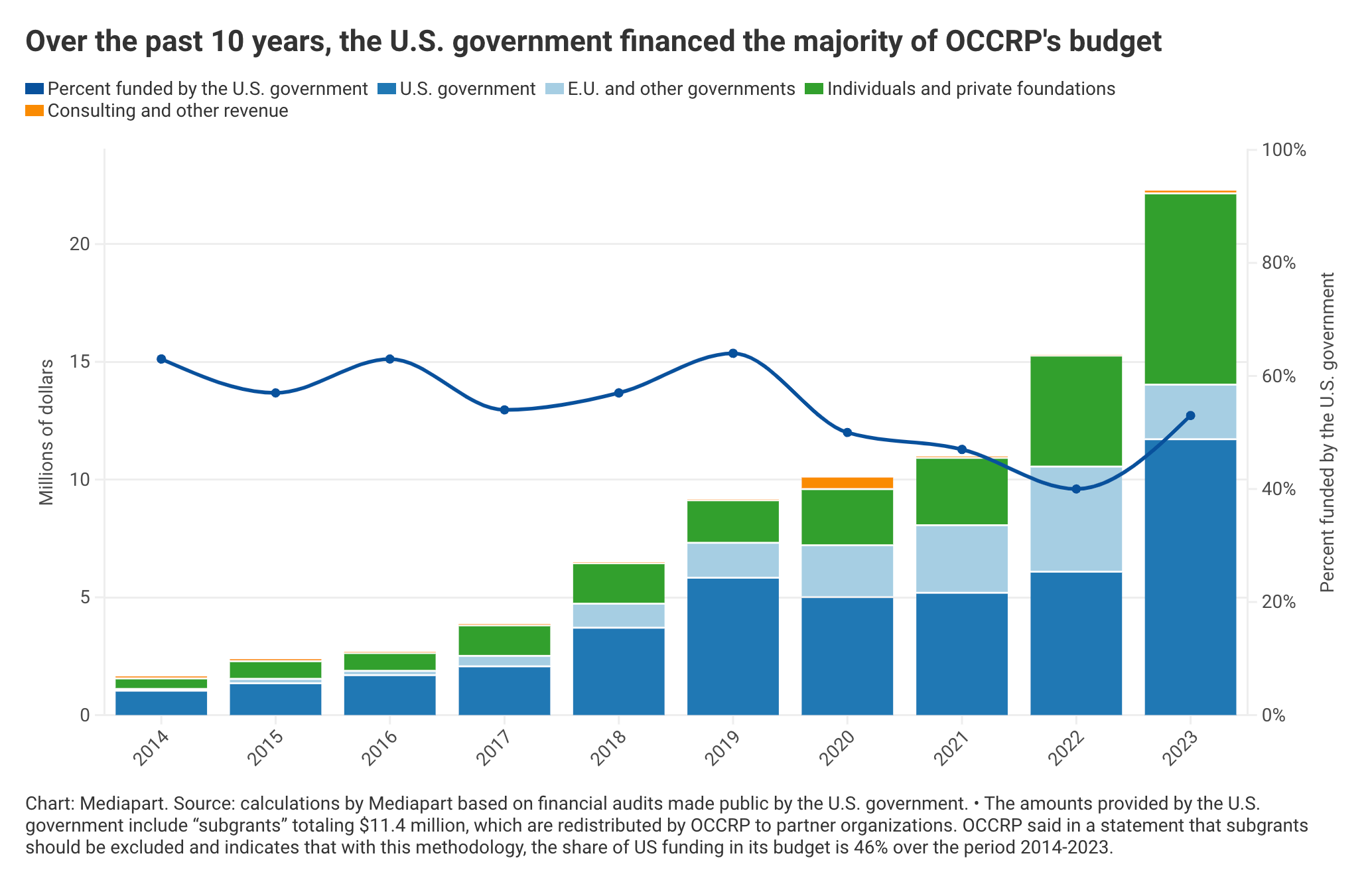

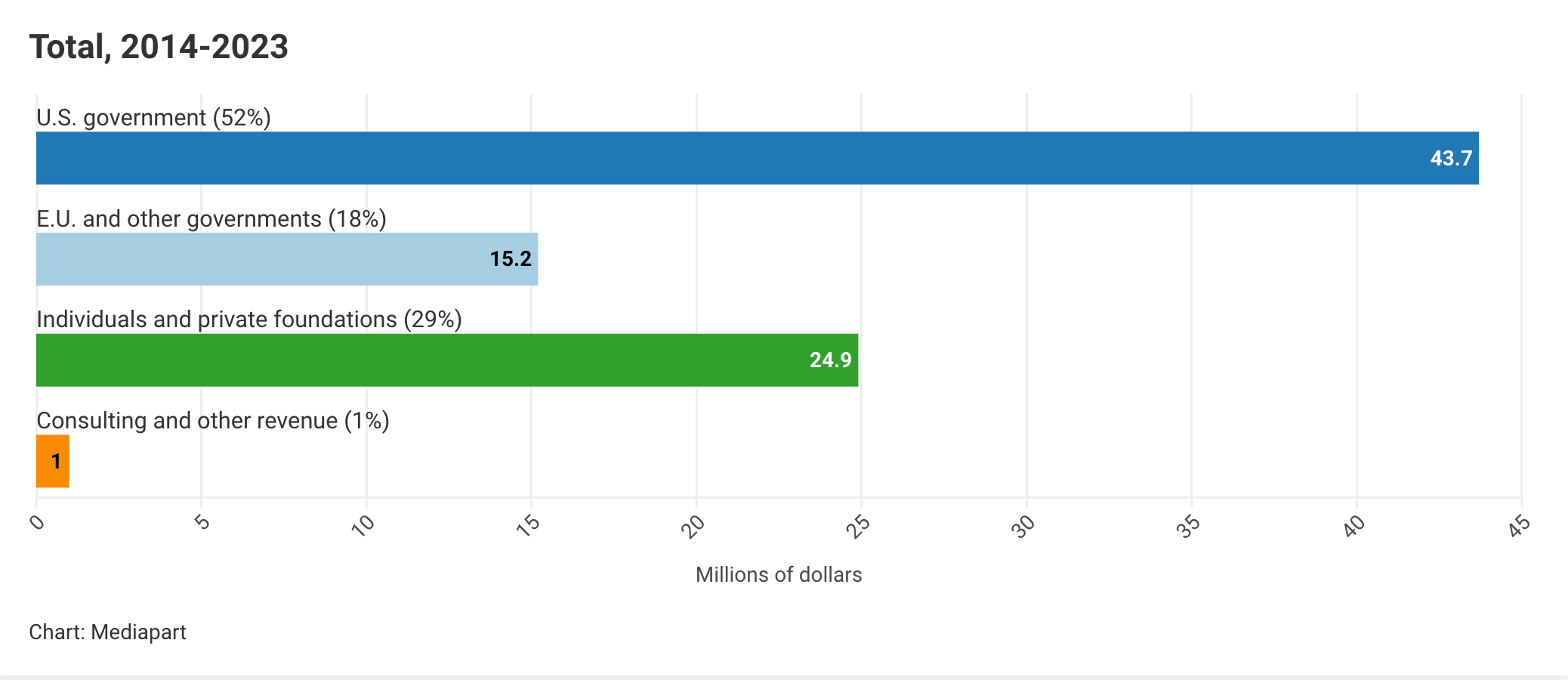

Between 2014 and 2023, the American federal government provided 52 percent of the money actually spent by OCCRP, and, since its founding in 2008, has shoveled at least $47 million (and committed $12 million more) to the ostensibly independent, nonprofit newsroom. Other Western governments—including Britain, France, Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands—have kicked in at least $15 million during the last 10 years. That’s according to a tabulation of OCCRP’s annual audit reports, cross-referenced with federal budget documents outlining disbursements. The review was conducted by a consortium of international news outlets, including Drop Site News, and is being published in conjunction with news outlets in Italy, France, and Greece. (Sullivan quibbled with the methodology behind the analysis, arguing grants that are passed through to other organizations shouldn’t be counted. Using his methodology, the figure still reaches 46 percent.)

While OCCRP has consistently disclosed that it accepts some money from governments, including the United States, the full extent of the financing has not previously been revealed.

The board of directors of OCCRP, in a statement to the consortium of news outlets jointly publishing this reporting, confirmed the U.S. is its major funder, though disputed the idea that they have been anything but up front about it. As its board told us in a statement:

What is true is that OCCRP has accepted funding from USG. We understand that reasonable people may believe that's a bad idea, especially since it is not the norm in journalism in the United States (although government support of journalism is not uncommon in Europe and elsewhere). This was thoroughly discussed years ago when OCCRP was founded. The Board at that time – which included several of us who remain on the Board and whose personal reputations as journalists and executives are impeccable – decided that it was worth the tradeoff for the investigative journalism OCCRP could produce with this financial support..

We understood, as perhaps you do not, that to do impactful, cross-border investigative reporting in many regions of the world would require not only philanthropic funding, but support from Western governments who understand that journalism is a prerequisite for democracy. That includes not only the United States, but many of the countries in the European Union.

From the beginning, we made sure that government grants had impenetrable guardrails that would protect the journalism produced by OCCRP. As we indicated in a previous response to your colleague, we are confident that no government or donor has exerted editorial control over the OCCRP reporting. Seventeen years later, we are entirely comfortable with our decision, and enormously proud of the journalism the organization and its partners have produced.

Sullivan was more blunt, stating that the idea that “the United States government has exerted control over the journalism OCCRP has produced" has "no evidence to support [it] … only insinuations, incorrect interpretations, and imputations.”

The work of OCCRP, often in collaboration with other newsrooms around the world, has been deeply impressive journalistically and at times they have done reporting at odds with U.S. national interests, including a look at how the Pentagon was relying on dodgy arms merchants to arm Syrian rebels. María Teresa Ronderos, director of the Latin American Centre for Investigative Reporting, said in an email that she “never felt that there were topics, issues or places that were restricted” when working with OCCRP. “Moreover, we have collaborated with them in stories that were particularly critical about US drug policies (series An Addictive War), or about US migration policies (Migrants from Another World) and they never expressed having a problem with this.” OCCRP’s reporting on Rudy Giuliani’s political work in Ukraine was cited four times in the whistleblower letter that led to President Donald Trump’s impeachment.

Others said they knew of and were unbothered by the U.S. government funding. “We are aware that OCCRP is receiving funding from the U.S. government,” said Georg Eckelsberger of the Austrian magazine Dossier. “In our experience there was no influence on the journalistic work of OCCRP and OCCRP-member-centers. The investigations we cooperated in were independent, objective and committed to high journalistic standards.”

But the extent to which it has been backed by the U.S. government has caused consternation among would-be or former partners, as well as one high-profile board member.

Upon learning of the extent of U.S. government funding through the course of its own investigation, the German public broadcaster NDR decided to pause future collaborations with OCCRP, according to an email from a senior editor at NDR. A spokesperson for the New York Times, which has worked on collaborations with OCCRP, said that the news organization did not disclose the nature of its funding to the Times.

OCCRP board member Lowell Bergman, the legendary investigative journalist portrayed by Al Pacino in “The Insider,” said that after he discovered the government connections he left the board around 2014. "I was overwhelmed with my commitments elsewhere. It was also then that I became aware of the U.S. government involvement. Because that was clearly a complicated issue, I expressed my concern to Drew Sullivan and others, and respectfully stepped off the board," Bergman said.

Many of the interviews and statements in this piece, including Bergman’s, were given to NDR, which initiated the investigation into OCCRP and later involved Drop Site and its European partners.

“Editors on all continents”

Despite its obscure name, the collaborative journalistic institution has reshaped global affairs with its investigations of enormous tranches of leaked documents: OCCRP did the Russia-focused reporting from the Panama Papers and played a key role in the Pandora Papers, the Suisse Secrets, the Russian Laundromat, and China Tobacco. All were game-changing exposés, all targeted largely at U.S. adversaries. Its collaborative approach has led to partnerships with more than 50 of the globe’s most influential media outlets: the Washington Post, Rolling Stone, The Guardian, The (London) Times, Der Spiegel, Le Monde, and so on.

In 2016, the year of the Panama Papers, USAID and other American government funding sources made up 63 percent of OCCRP’s budget.

The way it typically works: a journalist, sometimes working directly for OCCRP and sometimes part of its global network, will receive a leak of a cache of internal documents from, say, an offshore financial service provider, a bank, or some other entity with access to sensitive documents. Sifting through that data and transforming it from terabytes of unwieldy information into articles published in major papers around the world is the job of OCCRP. OCCRP has built a massive database, called Aleph, that includes data it has obtained as well as publicly available documents that are often difficult or expensive to collect and search.

The organization has more than 200 staff in some 60 countries and works as a hub for local reporters around the world. For collaborative projects, OCCRP not only offers its logistical, editorial, and research support, but also covers the costs for local journalists, including salaries, said Paul Radu, a co-founder. “We pay for the expenses of the story. Reporter has to travel somewhere, a reporter has to get some information from a database, and it costs $50. It costs that and that and that. We're covering those costs. And then we're also covering a salary for the reporter while working on the investigation,” he said.

“It's the first global investigative reporting organization,” Sullivan said. “We have editors on all continents. We have staff on all continents. And we're the first organization that's gone global. And we've participated in almost every major global collaborative reporting project.”

Sullivan initially disputed the idea that OCCRP had any single, primary donor, but then acknowledged the U.S. served that role. He subsequently pushed back on the notion that the U.S. was the majority funder, arguing that we should not take into account the money that OCCRP receives but then passes through to partner organizations. Using this methodology, the share of spending funded by Washington over 2014-2023 falls to 46.4 percent, not 52 percent, according to Sullivan.

Origins in Soft Power

How Sullivan first caught the attention of the U.S. foreign policy officialdom is itself a window into the purpose of the organization. It begins with a coup in the Philippines. State Department official Michael Henning had previously been stationed there. In 2001, the non-profit outlet the Philippine Center for Investigative Journalism (PCIJ) exposed corruption by then-President Joseph Estrada, a nationalist with a standoffish relationship to the U.S. The exposé led to an impeachment inquiry, which fell short. But it also produced major street protests, leading to his ouster in a coup. The journalist’s pen was not just mightier than the sword, but less embarrassing to wield on a global stage in an era where overtly U.S.-backed military coups had gone out of fashion (if not entirely out of the toolkit). Henning was a major booster of PCIJ—which has been the beneficiary of grants from the National Endowment for Democracy—relaying its effectiveness to his colleagues.

Henning was later posted to the American embassy in Bosnia, a region then recovering from the recent Balkan war. The U.S. was working to transition the region from state-centric, post-Soviet economies with warm relations to Russia to one friendly to markets, multinational corporations, and oriented toward the West. In an interview with NDR, Henning said he concluded while in Bosnia, “What we really need is an independent investigative reporting center. And I said, I know something because I served in the Philippines.”

Sullivan understood the assignment. "That's the big challenge with Europe, is to change these states from these patronage-type systems based on corruption to really democratic systems," Sullivan told NDR. Sullivan had also taken a circuitous route to Bosnia, starting out in engineering for a contractor to NASA, working with a security clearance. He first traveled to Bosnia in 1999 to train local journalists in online investigative reporting—starting with how to use a mouse.

He remained invested in investigative journalism in the region. “While stories in America were about quality of life,” he wrote, “in the Balkans they were about life and death.” Henning said that he connected Sullivan with PCIJ’s Sheila Coronel, so the two could swap notes.

OCCRP claims in the history section of its website to have been launched with a grant from the United Nations Democracy Fund, but the history is foggy, and that UN grant went to a different organization in April 2007 that predated the formation of OCCRP. It’s more accurate to say the first million dollars that made the creation of OCCRP possible came from the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs—known as INL, part of the State Department—in 2008. USAID conferred with former State Department official Dave Hodgkinson, who is now one of America’s top intelligence officials, tasked with overseeing the intel community’s relationships with “the private sector.” Henning said, “He was the, let's say, the guy with the money at the State Department who could make that happen.” The grant was routed to a legal entity called the Journalism Development Group, an LLC in Delaware, which birthed OCCRP. Though INL issued the grant, USAID managed it. Meg Gaydosik, the USAID official who took over the relationship from Henning, confirmed she had not only pushed to get funding for OCCRP internally but even helped re-write the group’s application for a major USAID grant. “It was from USAID,” said Gaydosik of the project’s key original support. Shannon Maguire, a former official with the National Endowment for Democracy, took over from Gaydosik, and continues to run the OCCRP file.

Henning said that getting funding for programs like OCCRP was made easy because their missions aligned with American interests. “This is the beauty of the Cold War. It didn't matter, you know, as long as you could identify our national security interest, all of a sudden there was money to feed babies,” said Henning.

“Mindful of how uncomfortable the relationship can be”

Maguire, the USAID official who now handles the OCCRP file for the federal government, said the government is proud of the work it’s done boosting the news organization. “We're proud that we're the first public donor, that USAID is the first public donor, and the U.S. government is the first public donor to assist OCCRP,” she said, adding that the government is cautious in how much it celebrates its involvement, “mindful of how uncomfortable, sometimes, the relationship can be in terms of, you know, providing support to OCCRP.”

Maguire and other USAID officials have attended OCCRP’s annual conferences. And while OCCRP’s board and Sullivan say there is an editorial firewall, the funding comes with a few strings—strings that are mandated by U.S. regulations but are nonetheless unusual for a news organization. The federal government can veto senior personnel, including senior editorial staff, as well as an “annual work plan,” according to Maguire and Henning. It can veto top hires. “If OCCRP needs to change key personnel, for example, the chief of party, which is Drew Sullivan, then they submit a request with a resumé and we review it and say, okay, this, you know, we approve your nominee for a new chief of party or whoever it is,” Maguire said.

Henning confirmed, “Who's the editor in chief or who's the CEO, who's the, you know, managing editor, etc. Those would be sort of a top tier of people that would be approved.”

In response to a question about the veto power of the U.S. government over editorial personnel, OCCRP’s board explained to NDR, “Such restrictions are common across all government grants,” adding:

It is important to note that the purpose of the key personnel provision has nothing to do with the editorial content of the grant but rather the administration of it. While editors sometimes are listed as key personnel, the USG is assessing their ability to implement the grant goals and manage the project, not oversee the editorial mission. In practice with OCCRP and its partners, no donor has ever vetoed any staff position and had they done so, it would not have affected OCCRP’s ability to control the editorial product. OCCRP or partners may not agree to a veto designed to change editorial processes and would likely decline the grant in that case.

“All OCCRP grants acknowledge donors have no right to interfere with the editorial policies and process of OCCRP,” they continued. “Moreover, donors usually want to avoid involvement in editorial decisions to prevent the appearance of influencing local politics.” In other words, it is advantageous for the U.S. government to fund journalism in its interest, but not interfere with or control it, because that would taint the results.

“Balancing the Russian Media Sphere”

All good journalists want impact, and OCCRP has delivered. “We've probably been responsible for about five or six countries changing over from one government to another government,” Sullivan said. (He identified four: Bosnia, Kyrgyzstan, the Czech Republic, and Montenegro.) “People do a lot of stuff to try to get that same impact. But investigative reporting actually does it.”

The breakthrough moment for OCCRP came with what became known as the Panama Papers. A German reporter, Bastian Obermayer, had been on the receiving end of an unprecedentedly large leak of data with extraordinary geopolitical implications. It was a cache of financial records exposing the offshore accounts of some of the world’s wealthiest people, many of them in an adversarial relationship with the United States. Obermayer worked with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which brought in OCCRP to help organize the data and recruit journalists to work on the project. OCCRP focused on the Russian angle, having previously played the lead role in what became known as “Laundromat,” an expose of the holdings of Vladimir Putin and those close to him. The work OCCRP had done mapping Putin’s wealth set the foundation for the follow-on reporting from the Panama Papers.

“What they did with the Panama Papers, a lot of that drew on the research [OCCRP] had done, the databases they had created as part of those reporting projects and helped to make the links even stronger,” said USAID’s Maguire, adding that the organization “should probably get more credit than it does for the Panama Papers.”

“OCCRP had dozens and dozens of reporters working on that,” said Sullivan.

“We had a very important role to play in the Panama Papers, where all the Russia side, the Putin side or these Eastern European oligarchs’ side and much more was actually done by” OCCRP and its affiliates, said Radu.

The reporting won the Pulitzer Prize (though OCCRP was not named as a winner). Putin himself, of course, was less impressed, claiming the leak and reporting had been an American intelligence operation. The U.S. denied the claim. Later in 2016, Putin, according to the U.S. government, authorized the hacking and leaking of data from the Democratic National Committee, an operation seen in intel circles as retaliation for the Panama Papers. Putin denied the claim, but said that it shouldn’t matter how the information got out. Sunlight, he suggested, was a good disinfectant, no matter who opened the window. "Does it matter who broke in? Surely what's important is the content of what was released to the public," Putin told Bloomberg News. "That's what the discussion should be around. There's no need to try to distract public attention from the essence of the problem with questions of secondary importance connected with the search for who did it."

Trump won in November 2016. During the lameduck congressional session, with bipartisan support, Congress expanded authorization for the State Department to take on Russian disinformation with heavy funding.

In 2017, tucked into a piece of legislation sanctioning Russia, Congress authorized another $250 million toward the program, adding that the money would also fund efforts “to build the capacity of civil society, media, and other nongovernmental organizations countering the influence and propaganda of the Russian Federation to combat corruption, prioritize access to truthful information.”

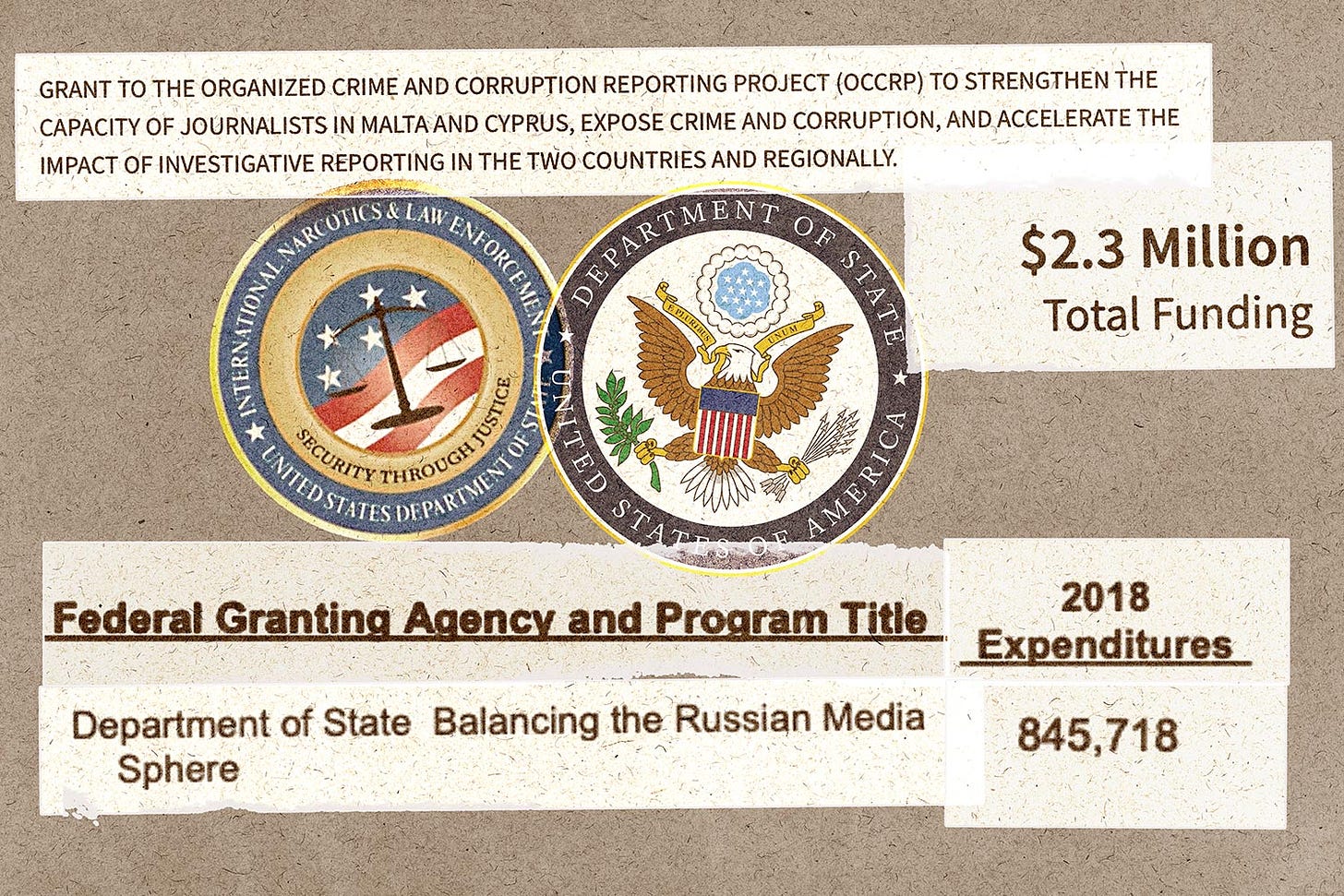

Two years prior, OCCRP received a large grant from the U.S. government for the express purpose of investigating the “Russia Media Sphere”—and in the following years, was granted funds to pursue several other topic areas and countries considered a priority by Washington. Between 2015 and 2019, the State Department gave $2.2 million to OCCRP for the purpose of “Balancing the Russian Media Sphere.” Between 2019 and 2023, OCCRP received $1.7 million, also from the State Department, for “Strengthening investigative Journalism in Eurasia,” a region that includes Russia and Belarus. In 2021 and 2022, OCCRP directed the international investigation, “Russian Asset Tracker,” based on the creation of the world's largest non-governmental database on the assets of Russian politicians and oligarchs.

In 2022, INL granted $1 million over two years to the journalism NGO to “strengthen the capacity of journalists,” “expose crime and corruption” and “accelerate the impact of investigative reporting” in Malta and Cyprus, two tax havens highly prized by Russian oligarchs.

During the same period OCCRP participated in the international investigation Cyprus Confidential. On November 14, 2023, the day after publication, Cyprus’s president announced the beginning of an investigation into possible violations of sanctions against Russia, revealed by the articles. Three weeks later, more than twenty FBI and FinCEN agents arrived in Nicosia to assist their Cypriot colleagues.

INL seemed to be satisfied with the completed work; the dedicated program on Cyprus and Malta was renewed the following September, with $1.3 million more dedicated to funding OCCRP.

“You couldn’t do that just with the free market alone”

OCCRP’s work may be obscure to the public, but inside the national security architecture it is well known. A window into its prominence opened a crack in June 2021, when the White House’s National Security Council gathered reporters for what’s known as a background briefing, where the identities of the officials speaking are to be kept confidential in the resulting reports, described only as “senior administration officials.” The briefing focused on a new memorandum laying out U.S. efforts to target global corruption, and one reporter asked:

Anti-corruption activists periodically urge the U.S. government to use its various assets and capabilities, including the intelligence community, to expose specific cases of corruption overseas, to name and shame corrupt officials — and the arguments they make are familiar — but also include not only a deterrent to corruption, but also a possible contribution to the promotion of democracy. Does the memorandum — does the program include any component that connects with that?

A senior administration official responded by saying, “Largely, the way that corruption is exposed is through the work of investigative journalists and investigative NGOs. The U.S. government — to my point earlier, in terms of the support we’re already providing — in some instances provides support to these actors. And we’ll be looking at what more we can do on that front as well.”

The reporter asked what “support” meant in that context, according to a transcript of the briefing.

“Sometimes it boils down to foreign assistance. There are lines of assistance that have jumpstarted investigatory journalism organizations. What comes to my mind most immediately is OCCRP, as well as foreign assistance that goes to NGOs, ultimately, that do investigative work on anti-corruption,” the official said.

In November 2021, Foreign Policy magazine hosted an event titled “Independent Media and the Advancement of Democracy,” and invited USAID chief Samantha Power to speak. In her remarks, she called OCCRP a “partner” of the U.S. government. “We have partners, the Organized Crime and Corruption Project is a major partner in reporting on the Pandora Papers and that the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists coordinated that. This OCCRP network, you couldn't do that just with the free market alone, right? Six-hundred journalists involved in the Pandora Papers effort: 75 from that OCCRP network and spending years going through three terabytes of documents. We have to think structurally about what are the means, again, to support those public goods,” said Power. “We work with independent media and local media around the world trying to enhance their financial viability.”

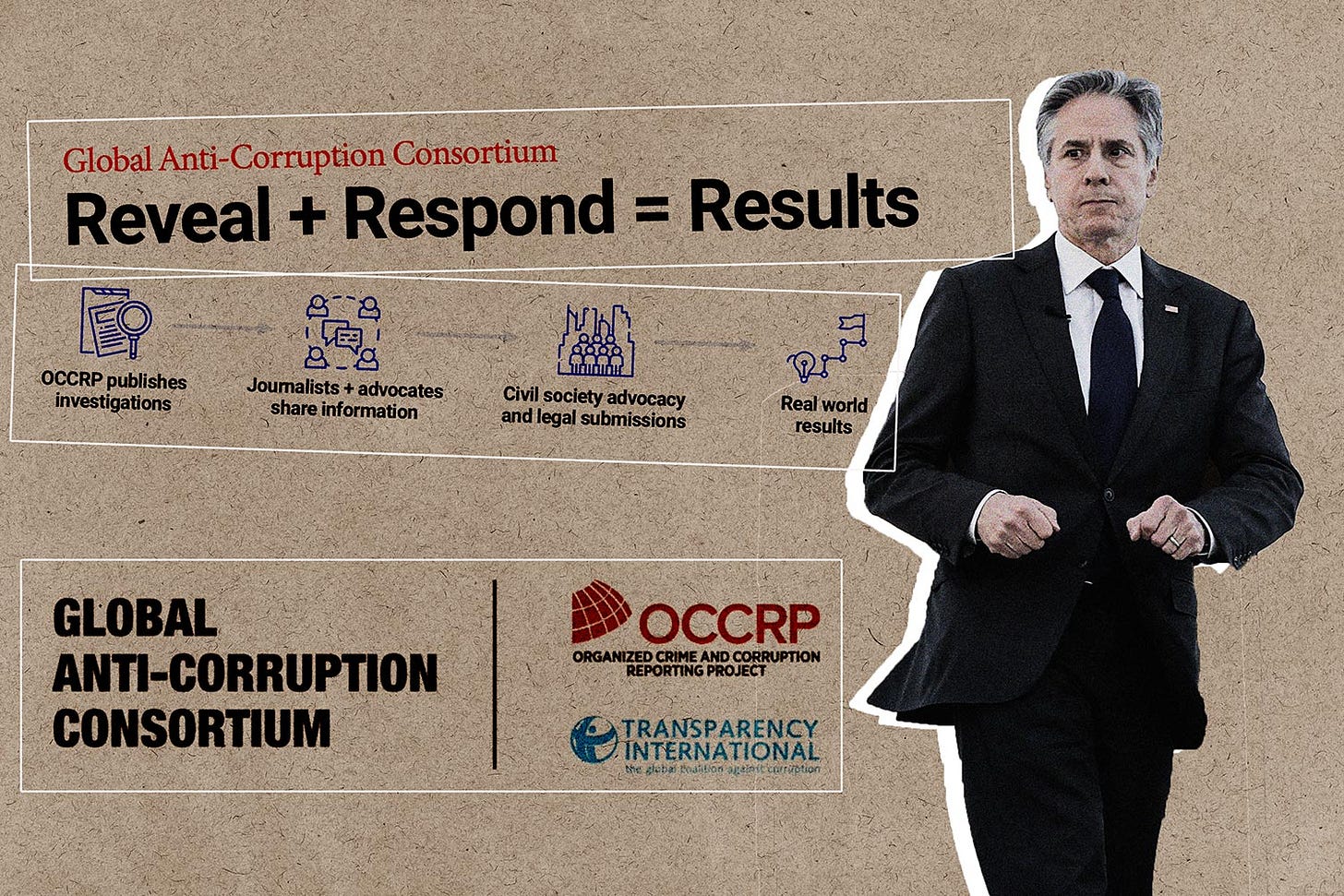

One example of this partnership is the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium (GACC), a program that weaponizes OCCRP investigations, trying to systematically trigger criminal investigations or sanctions proceedings based on the articles. GACC was founded in 2016 following a call for proposals launched by the State Department and won by OCCRP, in partnership with the anti-corruption NGO Transparency International.

The GACC is co-funded by four other governments and private donors, but the U.S. government is the largest contributor: it has so far paid $10.8 million to OCCRP under the GAAC, of which $3 million has been given as a subgrant to Transparency International.

The GACC has two activities. The first is to trigger, on the basis of OCCRP articles, judicial investigations, sanction procedures and civil society mobilizations, thanks to the support of Transparency’s local chapters, present in 65 countries.

The second is to lobby states to toughen their anti-corruption and anti-money laundering legislation. In May 2024, the OCCRP produced a report for the attention of governments about the best procedures for fighting intermediaries (such as straw men and lawyers) who facilitate the dodging of sanctions imposed against Russia. The report was produced in partnership with the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI), a British think-tank, and paid for by the United Kingdom's Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office. The RUSI has close links with the defense and security professions. One of its senior vice presidents is General David Petraeus, a former director of the CIA.

The fact that a journalistic organization would carry out such activities at the initiative and with money from the United States, even for a good cause, raises significant ethical issues. “While some initially found this approach controversial, it has since been adopted now by other media. We believe that GACC has proven to be highly successful,” replied Sullivan. “OCCRP recognizes that fighting corruption requires work by journalists, activists, law enforcement and policy persons. Investigative journalists benefit from exchanges with other types of actors, and vice versa. GACC helps convene such exchanges on occasion.”

OCCRP and Transparency claim to work independently, and that Washington does not prohibit them from going against its interests.

A GACC assessment report produced by OCCRP in 2021 at the request of the US government assesses this, though it has never been published. According to a summary that Transparency provided to us, the report identified “228 examples of real world impact,” of which only 11 concern “the Americas.” The number of cases related to the United States is not mentioned, but “the Americas” would have also included Central and South America. In 2013, INL poured $200,156 into OCCRP for “Project Mexico.” The State Department donated $173,324 to OCCRP to “reveal and combat corruption in Venezuela,” which is led by Nicolás Maduro, an enemy of the United States.

Transparency provided us with only one specific example of GACC action taken against the United States under the GACC: the NGO advocated for Washington to end the opacity that reigns in its internal tax havens (such as Delaware), after the United States was designated as one of the largest offshore centers on the planet by one of the investigations resulting from the “Pandora Papers”. But OCCRP did not participate in this article (produced by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists and the Washington Post), and focused, during the “Pandora Papers”, on its preferred areas: Russia, Central Asia and Eastern Europe.

In 2017, OCCRP recruited as “Chief of Global Partnerships and Policy” a senior American official, Camille Eiss, who had authority over the GACC. Just before her hiring, she was an anti-corruption adviser at the State Department. She returned there in 2022, to work in the office responsible for sanctions procedures.

Asked about this possible conflict of interest, Camille Eiss did not respond. “We hired Ms. Eiss because she is a talented thought leader in the anti-corruption space,” Drew Sullivan told us.

In any case, Washington seems delighted with the work accomplished. In a document published in December 2021 by the White House, the Global Anti-Corruption Consortium is presented as one of the initiatives that allowed the US government to “enlist the private sector as a full-fledged partner” and “unleashing private sector advocacy for anti-corruption reform”. At the same time, US Secretary of State Antony Blinken promised to increase funding for the GACC, and called on other governments to provide an additional $10 million.

Not All Journalism

Why fund journalists rather than simply send out law enforcement to uncover crimes? State Department official Henning said that reporters who are understood to be independent of the government sometimes have a better chance to coax cooperation from sources. “The beauty of investigative reporters and truly independent journalists—and independent in a serious way—is that people will talk maybe more to a journalist than they might necessarily to a government official,” he said in an interview with NDR. “So having journalists do this work lends a certain—reduces some fear and encourages more openness.”

“Some people that are aware of criminal activities, they also sometimes want to see justice done. But it's tricky if you're dealing directly with law enforcement,” he added.

In multiple statements provided in its defense, both the board of OCCRP and Sullivan argued that while government funding may be controversial, it is acceptable because the United States government does not exert direct control over the journalism, but instead believes that good journalism is essential to the health of global democracy. The U.S. has an interest in spreading and strengthening democracy and in combating corruption. Investigative journalism serves that purpose and is at risk of extinction; in the era of social media platforms vacuuming up billions of dollars in ad revenue, no business model for investigative journalism has arisen apart from charitable ones. (By the way, donations to Drop Site News are tax deductible.) Therefore, funding investigative journalism is in the national interest even if the U.S. doesn’t control the product.

Yet the claim that the U.S. broadly supports global investigative journalism as a matter of principle, no matter who is being investigated, is undercut by a rather conspicuous counter example, namely the U.S. government’s relentlessly hostile posture toward Wikileaks, which rose in tandem with OCCRP. Wikileaks encouraged whistleblowers to provide it with evidence of corruption and criminality, then partnered with news organizations around the world to publish its findings.

Wikileaks was launched in October 2006 and by March 2008, the U.S. military concluded the news organization was a “potential force protection, counterintelligence, operational security and information security threat to the U.S. Army.” It suggests that "identification, exposure or termination of employment of or legal action against current or former insiders, leakers or whistleblowers could damage or destroy this center of gravity.” In 2010, Wikileaks published “Collateral Murder,” video evidence of a U.S. war crime in Iraq, followed quickly by the Afghan War Logs, the Iraq War Logs, and then in November, Cablegate, the release of thousands of internal State Department cables. Some of the cables exposed extreme levels of corruption in Tunisia, sparking outrage that soon burst into full blown revolution. The Arab Spring was on. The State Department was not a fan. In December 2010, The Huffington Post reached out to State for a comment on a story about Wikileaks, and Alec Ross, a top aide to Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, circulated it to Jake Sullivan and other senior aides, according to documents obtained by the Italian investigative journalist Stefania Maurizi through FOIA litigation. “The HuffPo/Open government gang is driving me nuts,” Ross wrote. “They think Assange is some sort of hero.”

That month, under pressure from the U.S. government, Amazon, PayPal, Bank of America, Visa, Mastercard, and Western Union all cut Wikileaks off from services, attempting to cripple it. Assange spent years seeking asylum in the Ecuadorian embassy in London, where he took refuge in 2012. The bipartisan hostility to Wikileaks continued under Trump. In 2017, CIA Director Mike Pompeo plotted his kidnapping or assassination, according to Yahoo News. That didn’t come to pass, but the Department of Justice charged him with espionage for publishing classified information and spent years seeking his extradition. In 2019, a new Ecuadorian president handed him over to the British. Assange was arrested and jailed in the United Kingdom while he fought U.S. extradition efforts until cutting a plea deal in June 2024 that allowed him to return home to Australia.

Critics of OCCRP often parrot Putin’s caricature of the organization as taking direct orders from Langley. But that misunderstands the nature of American soft power, one top editor in Latin America, who has worked on collaborations with the global news operation, told Drop Site News.

“OCCRP doesn't have to provide the USG with any info to be useful to them. It's an army of ‘clean hands’ investigating outside the U.S.,” he said, asking for anonymity to as not to disturb relations with funders and colleagues. “But it's always other people's corruption. If you're getting paid by the USG to do anti-corruption work, you know that the money is going to get shut off if you bite the hand that feeds you. Even if you don't want to take USG money directly, you look around and almost every major philanthropic funder has partnered with them on some initiative and it gives the impression that you can only go so far and still get funded to do journalism. The truth is we don't know how deep the influence goes in some newsrooms.”

I imagine OCCRP has not made any mention of the data that Wikkileaks has found; it is very telling that the organization only spots corruption outside the US....it has not found any corruption in the DOD?????? Which cannot pass an audit?.

Very informative!