Israel's Start-Ups Struggle to Lure VC Capital Amid Escalating Wars

Amid economic decline and a struggling export market, its government sought to pitch skeptical venture capitalists around the world on the promised land’s tech scene.

Story by Owen Lavine

NEW YORK — On the 10th floor of 7 World Trade Center, venture capitalists, start-up founders, philanthropists, and Israeli government officials gathered several weeks ago to hear 20 Israeli green-tech start-ups pitch their companies to investors from Hong Kong, Washington D.C. and beyond. But with images of bunker-busters flattening Beirut apartment blocks flashing across attendees’ laptop screens and phones, hydrogen fuel cells were a secondary concern. The next day, Israel’s ground invasion of Lebanon would begin.

“What can I say? We in Israel, we still [do] not believe we are in this situation,” Avi Balashnikov, chair of the Israeli Export Institute, chuckled in his opening remarks to the nearly 90 attendees brought to New York by the Israeli Economic Mission to the USA-East Coast. “But events like this, with people like you, who came here to do business, not only to do business, but be involved in our life in Israel—to be here with you is the most efficient thing I can do in the last days.” (Israeli officials later claimed 200 people showed up.)

Among the attendees of the expo, dubbed “EcoBreakthrough: Israel's Global Climate Solutions,” was Michael Matsumura, a partner at the Japan-based, tech-focused Scrum Ventures. While Israel’s record for producing high-quality start-ups and technologies gives Matsumura confidence in its future, its wars are “definitely a concern,” he said. “I’d be lying not to say that.”

For Balashnikov and other heavyweights in the Israeli start-up scene, locking in start-up funding has become an increasingly urgent matter. Since October 7, data from Israel High-Tech, Venture Capital and Private Equity Data and Analytics (IVC), the Bank of Israel and the Israeli Innovation Authority, shows investment in the country’s tech sector is on the decline. Founders have been trickling out of the country and with workers across the country reporting for reserve duty in the IDF, 20% of whom are in the high-tech sector according to a July analysis, the labor market has been stretched thin. Amid all of this, the cost of war has cut into the government’s ability to buoy its tech sector—even leading some in the industry to call for an end to Israel’s wars.

For many companies, founders, and CEOs, “Israel’s resilience,” as reiterated by speakers at the event, might not be enough to keep their business in Israel, according to Jennifer Laszlo Mizrahi, a co-founder of the Mizrahi Family Charitable Fund and one of the few philanthropists who attended the event.

Some companies she has spoken to said relocating could make it easier to meet with their customers and investors or to attend trade shows. “I’m not sure how much more of this I can take,” Laszlo Mizrahi recounted colleagues telling her, mulling their exit from the holy land. She declined to name the companies considering leaving.

With the government spending more than $66 billion on its wars, as data from the Bank of Israel shows, there are fewer dollars to throw at the newest EV charger. Larger funds and philanthropists like Breakthrough Ventures and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation have declined to fill in the gap, Laszlo Mizrahi said.

“The government of Israel is dealing with a lot of poverty right now. A lot of people lost their jobs. A lot of people lost their homes. A lot of people had to be relocated in the north and the south,” she said. “The scarcity of resources with which to invest in things is a very real problem.” The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation as well as Breakthrough Ventures have not responded to a request for comment.

Israel has long been known for nurturing successful tech-startups. IVC defines an “Israeli high-tech company” as one that develops technology/intellectual property, has at least one Israeli founder, has a headquarters or some activity in Israel.

Through the Israeli Innovation Authority, the government awards grants to start-ups of upwards of 85% of their “approved R&D expenses,” according to the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Israeli defense spending, aided by billions of dollars from the U.S., has been another stimulant for the growth of Israel’s tech market.

While investor anxiety about Israel’s broader tech sector performance grows, its defense-tech companies continue to perform well. Among the high-dollar deals were Exodigo, a developer of underground mapping tech that has raked $75 million since February. Xtend, another driver of growth that specializes in drone-operating systems, has raised $40 million since May.

While Israel’s record for producing high-quality start-ups and technologies gives Michael Matsumura confidence in its future, its wars are “definitely a concern,” he said. “I’d be lying not to say that.”

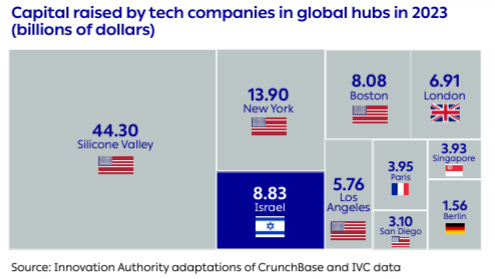

At the expo, government officials sought to reassure anxious investors. Pointing to data from the Israeli Innovation Authority, Anat Katz, Israel’s economic minister for North America, told the attendees there had been 45 new Israeli start-ups and $9 billion in new investment between October 2023 and August 2024. She also presented a bar graph showing investment into Israeli tech totaling $9 billion, right behind New York City and “Silicone” Valley—“a return to pre-Covid levels,” she said.

But further analysis suggests those numbers show Israel lagging behind the period of October 2022 to August 2023 by 4.7%. The data did not account for inflation, meaning the real numbers are actually much lower: Since October 7, Israel has outpaced its target inflation rate of 1%-3%, reaching 3.6% in August, according to data from the Bank of Israel.

Billy Wang, the head of investments at the Hong Kong-based Audacy Ventures, a VC firm with a portfolio that includes BugEra, an Israeli company seeking to reduce waste through genetically modifying black soldier flies, said Israel’s importance as a center of global innovation does not necessarily shield it from the consequences of its war.

“Energy is a global industry,” he said, speaking broadly about climate solutions. “So, if you’re telling me the only manufacturing plant is in Israel, I would be a bit hesitant,” he said, emphasizing that he’d apply that view “to any company, anywhere in the world.”

Balashnikov himself has acknowledged the worrisome picture for Israeli tech.

In an interview a week before the expo with Calcalist, an Israeli business outlet, he said Israel’s international business had suffered since October 7. “Economic boycotts and BDS organizations present major challenges, and in some countries, we are forced to operate under the radar,” he explained.

During his opening remarks, he recounted a conversation he had with Katz prior to the event, in which he asked her whether people would attend the event. “In the last week, some people cancel. You think that people will show up?” he told the attendees.

Despite the climate-centric theme of the event, the environmental toll of Israel’s wars did not come up. That includes the estimated 420,265 tons of carbon emitted by Israeli’s campaign in Gaza or the estimated 60 million tons of carbon required to rebuild the enclave, according to a study from the Social Science Network. In addition, no mention was made of the 118 billion cubic meters of natural gas Israel plans to drill from the Mediterranean.

Neither Balashnikov nor the Israeli Economic Mission responded to requests for comment.

‘Too Big to Fail’

As Israel’s tech sector struggles, it faces broader economic woes.

Late last month, Moody’s slashed Israel’s credit rating from an A2 to a Baa1. “The ratings would likely be downgraded further, potentially by multiple notches, if the current heightened tensions with Hezbollah turned into a full-scale conflict,” it said in a press release. Standards and Poor’s followed suit days later, a month after Fitch also lowered its rating for Israel.

While the high-tech sector has fared better than it did during from the first quarter to the third of last year, analysis from the IVC database, the leading database of its kind, shows the industry lagging behind 2021/2022 levels.

The declining investment and credit dips have convinced some in the Israeli tech sector to call for more government intervention—and even peace.

In August, Ron Abelski, a senior partner at Epstein Rosenblum Maoz, a VC-focused law firm, wrote an op-ed for Calcalist calling on the Israeli government to provide matching investments for the tech industry, arguing that the tech sector had “saved” Israel from Iran.

In an email to Drop Site News, Abelski said that “due to the ongoing conflict, many foreign investors have become temporarily hesitant” to invest in Israel. While he views the government’s actions to boost the high-sector as insufficient, “Israel’s position as a leading innovation hub is too big to fail and too important for foreign investors to turn their backs on,” he added.

Moran Chamsi, a partner at the Israeli VC firm, Amplefield Alternative Investments, who has also called for the Israeli government to commit more money to the Israeli tech industry, told Drop Site News in an emailed interview that “while I believe that peace can create a more favorable environment for economic development, I agree with the principle that peace should be pursued from a position of strength.”

Chamsi highlighted “growing anti-Israel sentiment in some international circles” and “talent shortages: the mobilization of reservists and the general shortage of skilled labor,” as constraining the Israeli economy.

Owen Lavine is a freelance reporter based in New York City. He has previously written for The Daily Beast and Labornotes.org.

Episode one of The Palestine Laboratory is up on our podcast feed today, free for everybody. It’s quite good and I think you’ll be glad you listened. If you want to binge the four-part series, that’s now available for paid subscribers. This is our biggest investment in a single investigative project to date. If you want to encourage us to do more of these types of projects, please upgrade or make a one-time contribution here. Become a paid subscriber now at DropSiteNews.com/PalestineLab and enjoy 20% off your subscription.

How much of that hi-tech is actually security stuff, i.e. weapons? The kind of weapons that dictators around the world, including in the US, want to use on their citizens.

My hypothesis is that even when the war is over, many of the skilled laborers in Israel will get out of dodge the first chance they get. I know that’s what I would do